Since I handed in my resignation, Claire (our HCA) decided to retire and left last week, three receptionists are heading off to uni, and Jane — one of the key clerical staff — is leaving too. All within a month. I’m out in two weeks. No replacements have been lined up. “It’s like rats leaving a sinking ship,” Jamie muttered.

It’s a bit sad, to be honest. Feels like the inevitable is finally coming for this place. We actually had a patient survey recently — 95% said their experience here was good or very good, which is worlds apart from when we started. Although I know that’s definitely an overstatement for how good we really are, things have got better. But it came at a cost. Burnout and stress amidst the usual silence from above. Still can’t get broken equipment replaced, contracts for staff or make any decisions. It’s all feeling very wobbly. And with no one coming in to replace me or the other 5 staff leaving, it looks like it’s about to collapse.

A Day in Clinic

This morning I see Roman, 28, with vomiting for 2-3 days. I assume it’s gastroenteritis, but he’s got upper abdominal pain and bilious vomit, with a bit of blood. Probably a Mallory-Weiss tear from all the retching. The veins lining the food pipe near the stomach rupture with continuous vomiting and it looks scary for patients but it generally settles. But he’s tender in the right upper abdomen and his breath catches when he takes a deep breath in and his gallbladder presses against my examining fingers — Murphy’s sign is positive. He is in pain when I ask him to jump up and down meaning there’s significant inflammation in the tummy. All this suggests he may have a nasty bout of cholecystitis, a gallbladder infection. Not what I expected in someone his age. I send him to the surgeons.

Then I see an infected boil, a hyperthyroid patient, and a couple of folks Western medicine can’t do much for, so I suggest exploring alternative healthcare perspectives.

Then there’s Dillon.

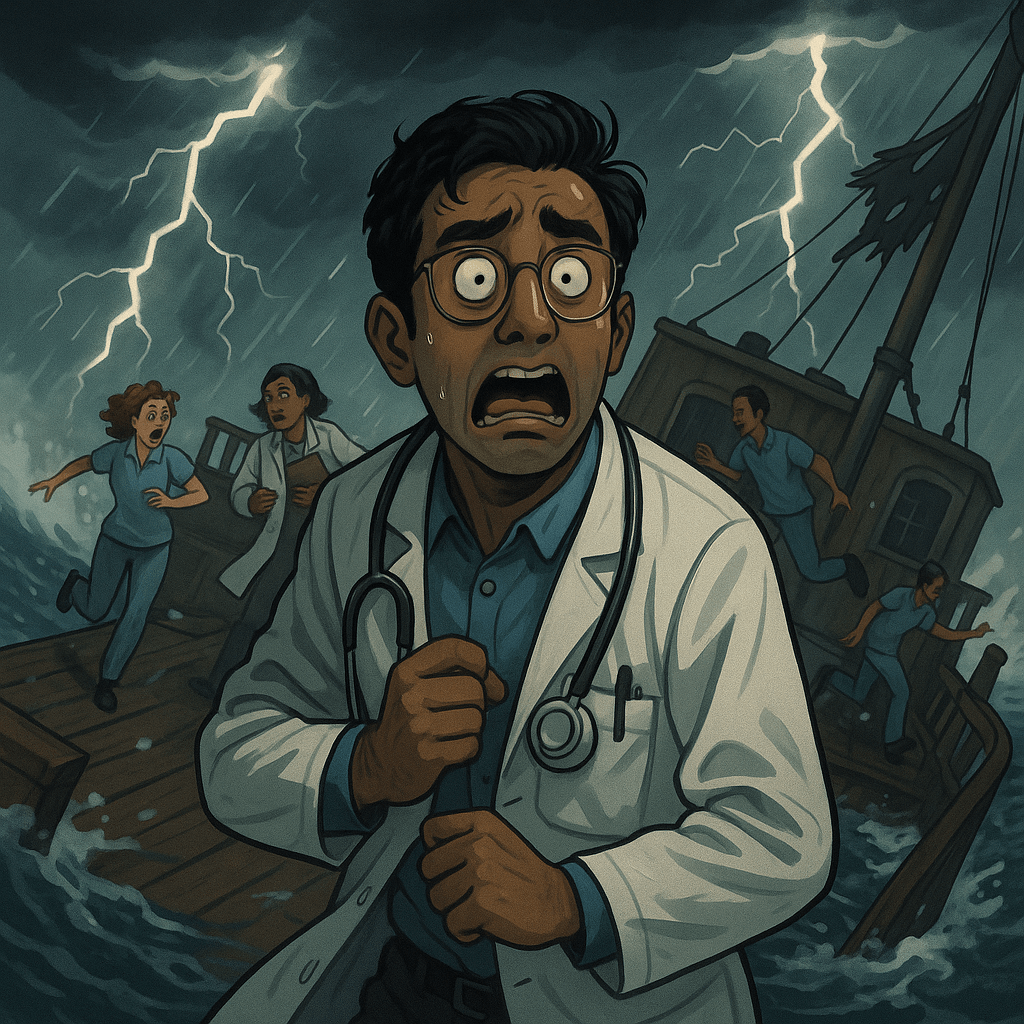

Dillon’s a sex offender who was released from prison a few years ago after a four-year stretch. He’s got a short fuse, punches walls or the steering wheel when he’s overwhelmed. His partner wants him to get help as he is hard to be around. He’s the first to admit it and wants to be a better version of himself earnestly. He’s not violent to her, but he says he feels numb all the time — except when rage takes over. He’s waiting on an ADHD diagnosis.

He could easily be portrayed as a monster. When I ask him about his past, he says his childhood was fine. No trauma.

But when I dig, he was raised by his mum alone, raising four kids alone. He never met his dad. Then he tells me he was bullied throughout school. He was full of rage, he says. Didn’t know why. He suppressed it until he was a young adult.

It’s interesting how people don’t always realise they’ve had a difficult start. He believed he never had overt trauma but he clearly had a hard time growing up. If you’ve never known stability, you don’t know it’s missing. No father figure, bullied every day — of course that leaves a mark. No grounding. No one to mirror healthy masculinity or teach how to deal with anger. That stuff gets buried until it explodes.

Offering Something

A lot of these guys can’t access mental health services, so I try to offer something. I mention a running app — Couch to 5Km, something free they can do with headphones to get them exercising.

I suggest finding community — like the local men’s shed that teaches woodwork. And hobbies. Hobbies help bring you into a state of flow — away from your thoughts, into your body, into something that feels safe.

And I always mention one of my favourite Gandhi quotes: The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service of others. I say, “Just help someone. In a small way.” Dillon tells me he’s going to bake cakes for his neighbours this weekend. Not what I expected him to say, but that’ll do.

On “Evil”

It made me think back to my yoga teacher training — where I learnt that in Sanskrit, there’s no word for “evil” in the way we use it in English. The concept of “evil” is more nuanced and context-dependent, often understood not as a cosmic battle between good and evil, but as a matter of ignorance, imbalance, or disconnection from dharma (one’s personal duty in society based on what’s needed and one’s interests, skills and talents i.e. one’s raison d’etre). Then there’s adharma, which means going against your nature or purpose and the butterfly effect that can come from that. ‘Something’s missing,’ or frustration and irritation you don’t understand. It builds up. There’s no cosmic stamp of “evil” on a person. No irreversible branding. If you are clasped in the unyielding hold of destitution, it’s very hard to even begin knowing what your dharma is. Your primary concerns are safety, food and shelter.

That really stuck with me. Most of the so-called “bad people” I meet are just scared, stuck, or broken in ways that no one ever helped them mend. They develop coping mechanisms which damage themselves and sometimes others. That doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be held accountable — but it does mean they’re still human.

And Finally, Ashmita

A bit later, I have a call with Ashmita, our clinical director. She’s one of the good ones — a GP trying to bridge the gap between the ground and the execs, who mostly operate on another planet. I wanted to speak to her about risk mitigation plans for when I leave, to get ahead of the looming staffing crisis. But before we even get there, she tells me she’s resigned. She spent the last 3 days crying and then came to a decision. She finally handed it in yesterday and feels relieved. She said her value of integrity had been challenged too many times, and she no longer felt aligned with how the organisation does things.

I’m not surprised. But I am. I release an exasperated chuckle. One by one, the wheels fall off. The rug’s about to be pulled from under the whole place.

And amid all that, Dillon — the sex offender — is baking banana bread for his neighbours.