I wake up and lie in bed. Can’t bring myself to get up and do anything useful. Decide to get my phone and scroll. Un-mindful medic.

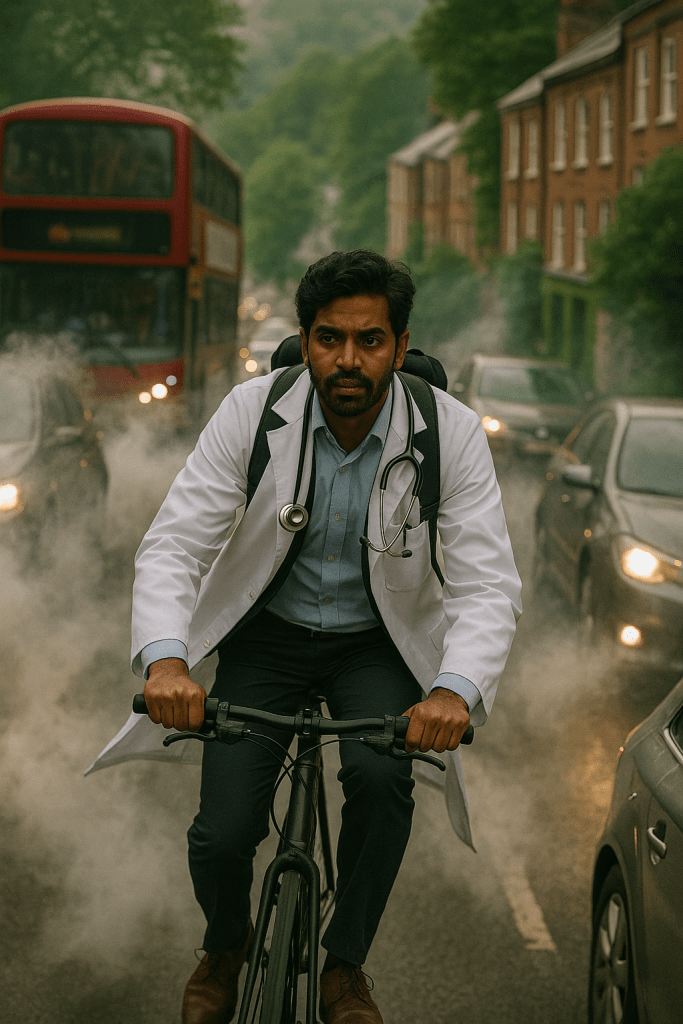

Eventually I contemplate if I can even be bothered to cycle into work.

I hear David Goggins’ voice:

“The only way you gain mental toughness is to do things you’re not happy doing.”

“Pain unlocks a secret doorway in the mind, one that leads to both peak performance and beautiful silence.”

Better get on me frigging bike then.

As I cycle in, there is the most amount of traffic I have seen in a long time. Not only that, there are random blockages—like a lorry in the middle of the road emptying industrial-sized bins, with cars literally driving on the pavement to try and get around it more quickly.

I chuckle as I nip past it. “To David Goggins,” I mutter to myself.

I arrive and say hello to reception—they’ve obviously heard I’m leaving, as they’re acting weird. No time to address the elephant in the room though. I leave them with the elephant and head to my room for clinic.

Today I see Jake again, first time in a while. I see from his psych letters he’s had a diagnosis of autism confirmed, and paranoid anxiety, for which he’s been started on sedating antipsychotics.

I learn of his childhood—his father left when he was four years old, and his mother was left homeless. They were sofa surfing for years. He was bullied his whole life because of his fractured skull birth deformity. They called him “subnormal,” and he struggled with being different and having low confidence. Ever since then, he has always been paranoid about what people think of him. He has felt life has not been worth living since he was eight. He left his mum when he was 16 and moved into a house full of drug users, who told him that as a bloke you should shut up, get on with things and never ask for help. That’s when he started self-medicating with booze.

Recently, he has been accused of being a paedophile because of the way he looks, and was assaulted because of this, apparently. His paranoia has become worse, and sometimes he has binges with multiple bottles of spirits in a day.

He’s been doing well off the booze lately. He’s always been fascinated by facts and learning things—biomedicine, botany, human anatomy, psychology—and he can retain information easily. He’s also studied woodwork, metal work, and scrapping. Of some concern, he does also know how to make explosives. He finds he becomes obsessed with learning one topic before moving on to the next.

Jake sees, in the periphery of his vision, a figure he describes as “death knocking on the door,” who disappears when he looks at him. He says he has to accept that something in his brain is not functioning normally. He believes he will never feel worthy and will always worry about what others think. He also says he doesn’t want to be alive—but when he is sober, this is not something he would act on. And yet, reassuringly, he also sees his life as a spiritual war that he must keep going with.

“Jake, I know you worry about what other people think, but do you think it is realistic to think that everyone in the world will like you? For the record, I think you are an incredible human being. Your story to getting here is both painful and inspiring. Yes, you have your demons—but so do we all. Despite all your lifelong adversity, you remain a fundamentally kind, incredibly caring, good person with talent that cannot be muted. I truly mean it, and I don’t say it lightly.”

On his way out he asks for a foodbank referral- I will arrange this but warn him there’s a waiting list.

At lunchtime, the manager, Jamie, pops in and I explain my situation to him and why I want to leave. I explain that he is one of the reasons why I have stayed so long, and that I do have a fondness for the practice, but I just can’t see how it’s going to work long-term for me.

“I know this must come as a surprise to you,” I repeat, as I did to Ritu.

He looks at me comically. “Not really.” Same response as Ritu. He chuckles. Jamie gets it. He feels the same—we are working with no freedom to make quick decisions needed to improve things. It is stifling and frustrating. And we are not listened to.

More validation.

I speak with Ritu at lunch. She seems a bit sheepish. Management have declined my request to reduce my hours, but they have agreed to give me leadership time starting ASAP. I think she’s unsure how I’ll respond. I don’t give much away—I’m happy I might be able to change things around here for my notice period, but it still doesn’t change the fact I want to reduce my hours and probably leave.

“The only way you gain mental toughness is to do things you’re not happy doing.”

I think this needs a timeframe caveat, David. And my timeframe feels like it’s almost up.

This weekend, I’m shooting up to Scotland again—this time for a UK-wide GP conference on British Medical Association (our union) policy. My expectation is that it will be dry as hell, but it’s in Glasgow where I used to live, so I can see old friends, my best mate is going, and part of me knows I need to engage with processes that ignite change: something we are in need of.

Maybe what I’m looking for isn’t policy change, but permission to start again.